Illustration from "Albumasar’s Introductorium in Astronomism" (1513)

Haga clic aquí para ver una traducción automática en español.

2025 is another rich year of discoveries about my family history, but this may be the most wondrous finding yet! Poking around FamilySearch's Full-Text Search (previous reports are here, here, and here) led me to find via Google my 11th-great-uncle, Antonio Sánchez de Cozar Guanienta (c.1634-1698), a priest who likely wrote the first book on astronomy in Colombia!

While Googling some conquistador mentioned in a chaplaincy record, I found an article about his descendant, "A mestizo cosmographer," who wrote about the cosmos and his own family history!!! Antonio's surviving 1696 manuscript, Tratado de astronomía y la reformación del tiempo (Treatise on Astronomy and Reforming Time), which the Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia has digitized, is a refreshing breath of culture from the suffocating Spanish colonial era. The unanticipated bonus is Antonio taking pride in his mixed Spanish and Indigenous heritage, which few of his contemporaries seemed to share. (A few other distant relations of mine, Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, Don Diego de Torres, and Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita, are rare exceptions.)

Have no mistake, Presbyter Antonio Sánchez de Cozar Guanienta could not be mistaken for his near-contemporary, Isaac Newton, or even Neil deGrasse Tyson. The historians who studied Antonio's manuscript since the 1860s viewed his work as an obsolete oddity. Somehow Cuban leader and poet José Martí read it and wrote a scathing put-down: "His style is not in any way literary — but mixed-up, laden with inexcusable repetitions, and very poor." More recently, J. Gregorio Portilla and Freddy Moreno (2018) reappraised the Tratado's scientific content, while Sergio H. Orozco-Echeverri and Sebastián Molina-Betancur (2021) explored the historical, intellectual, and even genealogical background that led to Antonio writing the Tratado. So let's dive into this ancient intellectual in my Colombian family, from an era when Massachusetts still obsessed over witchcraft trials.

It's easy to dismiss Antonio's work as goofy medieval dogma masquerading as learning. He did not stray from Ptolemian and Counter-Reformation teachings: The Earth was the unmoving center of the universe, the Sun, Moon, and five visible planets circled around it, and the outermost "Empyrean" sphere, which was the home of God, angels, and blessed souls, also stayed perfectly still. As the roving heavenly bodies passed through zodiacal constellations, Earth was impacted to varying degrees. God created the universe a few thousand years before, and two major cosmological bookends of history were the total solar eclipse experienced worldwide when Jesus Christ died on the cross, and the foretold Apocalypse when "stars of the sky fell to the earth." Antonio treated all of this as gospel, so to speak.

To his credit, Antonio made some direct observances of the skies, probably with an astrolabe, which resulted in some inventive ideas. He thought the celestial spheres could move without "angelic intelligence" or a "prime mover," which was a big departure from Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas. Antonio imagined the heavenly bodies as protruding, pointy "knots" on the spheres, which offset the sphere's centers of gravity and helped them perpetually move. Sometimes the knots got stuck on neighboring spheres, which is why planets are sometimes "in retrograde." (Don't forget, retrograde is apparent movement, not reality.)

After Antonio observed the movement of Kirch's Comet and Halley's Comet in 1681-1682, he theorized that comets were part of an "incognito" sphere between the Moon and Mercury, which explained why the Moon seemed to pass through the comet's tail and comets suddenly appeared and disappeared. Unfortunately, Antonio's separate section detailing the motion of comets is missing, so his theories aren't fully fleshed out. Orozco-Echeverri and Molina-Betancur suspect this and other sections on the structure of the Earth and the celestial spheres' motion were intentionally removed (p.315), which makes sense to me, given that they deviated from previous established theories.

Antonio tackled another three main topics: Standardizing when Christians should celebrate Easter, so it would not coincide with Jewish Passover, recalculating the length of the sidereal year (he was off by 75 seconds), and figuring out the birth year of Jesus Christ. The articles I linked to above spell out the first two topics, but I'll briefly talk about Antonio's historical chronology. After determining that the "actual" year is 44 seconds longer than the Gregorian calendar (and both are longer than the real answer), Antonio recalculated the "seven ages" of Earth, which numerologically match the seven days of Creation, and the 7,000 years allegedly allotted between Creation and Apocalypse.

For funsies, here's Antonio's proposed historical chronology, which I'll share in "AM" ("Anno Mundi," Antonio's calculation of years after Creation) and approximate equivalents in BCE / CE:

First Age of Earth — Creation to the Great Flood: 0 - 1656 AM [3821 - 2165 BCE] The Hebrew calendar claims Creation took place in 3761 BCE. Of course, both calculations ignore actual reality and the billions of years that preceded mankind.

Second Age of Earth — The Great Flood to the Vocation of Abraham: 1656 - 2023 AM [2165 - 1798 BCE]

Third Age of Earth — The Vocation of Abraham to the Law of Moses: 2023 - 2453 AM [1798 - 1368 BCE] Of course, we lack historical proof of Abraham and Moses's biblical biographies.

Fourth Age of Earth — The Law of Moses to the Captivity of Jerusalem: 2453 - 3362 AM [1368 - 459 BCE] Current historians usually say Babylon conquered Jerusalem in 586 BCE.

Fifth Age of Earth — The Captivity of Jerusalem to the Birth of Jesus: 3362 - 3821 AM [459 BCE - 0 CE]

Sixth Age of Earth — The Birth of Jesus to the Apocalypse: 3821 - 6000? AM [0 - 2179 CE] Antonio did not specify when the Apocalypse would take place, but I assume it is a literal thousand years before the Last Judgement.

Seventh Age of Earth — Apocalypse to the Last Judgement: 6000? - 7000? AM [2179 CE - 3279 CE] Antonio did not specify this period, but I assume it's a literal Millennium. In reality, Earth has over a billion years before the Sun is expected to expand and swallow it up.

Antonio's partial timeline (folio 59 r.), including the Virgin Mary's birth (3806 AM / 15 BCE), Jesus's birth (3821 AM / 0 CE), and Jesus's death (3855 AM / 34 CE). Antonio thought Matthew 27:46 "proved" that Jesus was "33 years, 3 months, 14 hours, and 14 minutes" old when he died. (folio 59 r.-v.)

Antonio had no false modesty, since he worked on the manuscript over 20 years, and as Portilla and Moreno point out, he wanted the Pope to seriously consider his calendar reforms and formally requested the King of Spain to pay for the printing. There's no indication that Antonio's writings were ever received, let alone seriously considered, but he made sure to preface his manuscript with his genealogy, to prove that he had the inborn, prerequisite "nobility" to deserve an audience.

The family history written by Antonio Sánchez de Cozar Guanienta is priceless (and I am grateful for the transcription by José Gabriel Sterling), because there are few documents written by, or even concerning the colonial inhabitants of Santander Department, Colombia. He begins by saying he lived in Vélez but was born in Mochuelo, the small settlement that later became the town of San Gil, and then he immediately boasts of his elite Indigenous ancestors:

"...[C]hance has placed me in the family and blood of the Indians who reigned in these kingdoms before the most felicitous empire of your Royal Service crowned them. Because my mother, Isabel Gómez Pavón Guanienta, is the great-great-granddaughter of Doña Juana Páche Guanienta, daughter of Guanienta Déyroré Ororí, the highest Monarch that was in this New Kingdom [of Granada, a.ka. Colombia]. His name meant 'Great Lord Cacique, Grand Monarch, Golden Head.'"

This is jaw-dropping!!! Antonio was the direct matrilineal (and therefore legitimate) descendant of the Cacique Guanentá, who was the supreme leader of who we now call the Guane Indians, a confederation of 31 chiefdoms across Santander Department, stretching from roughly what is now Vélez to north of Bucaramanga. Antonio went so far as to add the name "Guanienta" to his name and his mother's name, to pay homage to this noble ancestor. Guanentá ruled from the lofty heights of Xérira (now Mesa de los Santos), which overlooks the majestic Cañón del Chicamocha and is the second-most active earthquake zone in the world! Five centuries later, the breath-taking heights, frequent seismic activity, and surviving Guane cave art still leave visitors and locals alike in awe.

The historical record of the Spanish conquest of the Guane is pretty sparse, but in January 1540, Martín Galeano (coincidentally, another ancestral uncle of mine) led an army from Vélez to the heart of Guane territory. While the Guane stood no chance against Spanish Guns, Germs, and Steel, they did use effective ambush tactics before two big defeats at Macaregua (roughly near San Gil) and Chanchón (roughly Socorro).

It's not clear to me when Guanentá died, or whether he died in battle or took his own life to escape capture, but this cacique has since lived on in santandereano memory as a worthy but doomed opponent. Ismael Enrique Arciniegas romanticized Guanentá's defeat in a famous poem, and this is the ending (which rhymes in the original):

In front of the arquebuses the [Guane] ranks broke,

The cacique climbed a cliff showered with splendor,

When his quiver lacked the last arrow.

He valiantly tore his crest of red plumes to pieces,

Threw his wooden bow at the invaders

And from a height, over them, he fell to the river.

The Cacique Chanchón led a Guane revolt in 1547 which was immediately crushed by the Spanish, according to Presencia de un pueblo by my grandfather, Rito Rueda Rueda. Then, a major smallpox epidemic in 1558 killed off a large portion of the Indigenous people. Today, many local Guane caciques' names live on as names of locations, and even today the inhabitants of San Gil refer to themselves as guanentinos, in honor of the highest-ranking cacique.

Turning back to Antonio's narrative, his brief remarks on Guanentá may be exaggerated or partially invented, but perhaps they are a distant reflection of the Guane perspective of conquest:

At the time of the Conquests (being Emperor, King, and Lord of more than one hundred Caciques, Kings, or Lords), ... [Guanentá] left his palace in haste on the shoulders of his vassals (as he was accustomed to being carried) in a golden chair and with a golden crown. The Inca King of Cuzco, who was already close to conquering the entire new world under his dominion, [was] in what is now called Popayán, a little over 150 leagues away. Of [Guanentá's] palace, the four corners of carved and solid marble remain to this day at the site we call the Quebrada de los Santos...

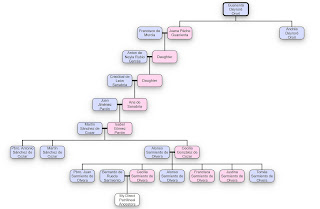

Antonio concludes that after Guanentá heard of the Guane defeat, he "retired to his palace, and since death overtook him before they dominated him, he died without the merit of baptism. His children, Don Andrés Déyroré Ororí and the aforementioned Doña Juana Páche, were found alive and they were the first Christian caciques…” Juana Páche Guanienta had the illegitimate daughter of a conquistador, Francisco de Murcia of Vélez, and that is the start of Antonio's family tree.

A 1643 document in Colombia's Archivo General de la Nación describes how a certain "Don Andrés" stepped down as cacique of Moncora (now the town of Guane) "because he was very old, deaf and handicapped by illnesses." The spouse of Andrés's sister Juana, Andrés Guaracabo, petitioned colonial authorities to be the next cacique, and by 1645 was listed as "the governor of Guanentá." It's unlikely this Andrés and Juana were the children of Guanentá, as they would have been over 100 years old by the 1640s, but perhaps they descended from the original "Christian caciques"?

Part of why Antonio details his Indigenous ancestry was to request that the king of Spain appoint his mother or brother as the ruler over the settlement of Guanentá, and grant "a title of their lordships with perpetual succession to all their descendants." That way, "by right of my maternal line," Antonio could gain access to a "treasure of gold that has been hidden here since the conquests... This belonged to my ancestor Guanienta, ... with which he ordered his burial in a vault, the location of which the Indians have hidden from us, judging that we would profit from it without rewarding them." Indeed, I don't blame the Guane for keeping this information from Antonio.

Muisca gold diadem at the "Thought and Splendour of Indigenous Colombia" exhibit, Montreal Museum of Fine Art, 2023

Antonio Sánchez de Cozar also covered his descent from multiple Spaniards, starting with his great-great-great-grandfather, the conquistador Francisco de Murcia (c.1509-1574), who as his name suggests, came from Murcia, Spain. Arriving in the Americas around 1530, Murcia was among the first settlers of Venezuela, then joined the expedition of Nicolás Federman (1536-1539), and helped found the city of Bogotá. According to historian José Ignacio Avellaneda, Murcia eventually settled in Vélez, exploited the encomiendas of Iroba, Guanentá, and Neacusa, and even though he was illiterate, served as the alcalde of Vélez. Besides having two children with Juana Páche Guanienta, Murcia also married a Spanish woman. His military service was memorialized by his criollo son Francisco in méritos in 1580. As the historian Enrique Otero d'Costa pointed out, Francisco de Murcia should not be confused with a similarly named conquistador, Francisco Gutiérrez de Murcia, who came to Colombia with the 1540-1541 expedition of Lope Montalvo de Lugo.

An unnamed daughter of Juana Páche Guanienta and Francisco de Murcia had an illegitimate daughter with another Spaniard, Anton de Neyla Rubio Garcés. I have not found any documents on Anton, but Antonio Sánchez de Cozar claimed he was from Aragón and a "descendant of the kings of Navarra," who was killed in battle by rebelling Muzo Indians.

Anton's unnamed daughter married Cristóbal de León Sanabria, a conquistador from Zafra, Spain. Sanabria wrote up his méritos in 1584-1585, and was put on trial in 1580 for "cruelties and homicides, committed in the indigenous communities of Tunja and its jurisdiction." Antonio Sánchez de Cozar claimed that Sanabria's grandfather, Francisco de León Sanabria, received royal cédulas for privileges in 1503 and 1509, but I have not verified that yet.

Sanabria's daughter, Ana de Sanabria, married a Spaniard named Juan Jiménez Pavón and died with five years of marrying, according to her grandson, Antonio Sánchez de Cozar. Juan Jiménez Pavón then resettled in the port of Gibraltar, Venezuela, where he had a second family, and he and his son served as alguacil mayor (chief constable). Antonio wrote that his half-uncle died over 30 years before, "in defense of your Royal Crown at the hands of the English." That likely means the pirate Henry Morgan's raid of Gibraltar, Venezuela in 1669.

That leads us to Antonio's mother, Isabel Gómez Pavón Guanienta, who married Martín Sánchez de Cozar, a native of Villanueva de los Infantes, Castilla–La Mancha, Spain. The 17th-century genealogist Juan Flórez de Ocáriz briefly mentioned Antonio's parents in his work: "Martín Sánchez de Cozar and Isabel Gómez de Sanabria, neighbors of... Vélez, with young children, and the oldest a scholar at San Bartolomé in Santa Fé [Bogotá]" (Vol. 2, Arbol XV, p.290). Orozco-Echeverri and Molina-Betancur suspect that this unnamed "scholar" could be Antonio.

El Tribuno de 1810 by Adolfo León Gómez claims that Antonio's paternal grandprents were named Martín Sánchez de Cozar and Cecilia González, and through FamilySearch's Full-Text Search I found a 1604 baptism record from Villanueva de los Infantes of Antonio's likely uncle: Francisco, son of Martín Sánchez de Cozar and Cecilia de Montoya (which was her father's surname).

FamilySearch researchers have also a great job of compiling digitized records about Antonio Sánchez de Cozar Guanienta. He was baptized in Guane in June 1634 (the exact day is missing, since the page is ripped), and the entry is labeled on the side "Ant.o hijo de Martín Sánchez español" [Antonio, son of Martín Sánchez, Spaniard]. "Ant.o Sanchez de Cozar Juanenta" was listed in a 1685 baptismal record from Vélez as having baptized an orphan named Juana out of "urgent necessity," and he baptized other Vélez children from 1692-1696. Finally, a notarized record from 1717 mentioned that the priest who first ran a particular chaplaincy, "Bachiller Antonio Sánchez de Cosar, Presbítero," had died in 1698, which is about two years after completion of the Tratado. That's how we can build the vague outlines of Antonio's life, and honestly, you can see how most surviving 17th-century sources can be pretty dry. Antonio the scientist vividly stands out in a society of endless soldiers, plantation owners, birthing wives and mistresses, and clergy.

There's one more interesting aspect of Antonio Sánchez de Cozar Guanienta: he liked to draw! In diagrams featuring the Moon and Sun, he made sure to add whimsical faces, like the example on lunar eclipses below (folio 109 r.).

Perhaps following in the tradition of illuminated manuscripts, Antonio also added fanciful marginalia like arranged groups of twinkling stars and elaborate swooshes. In two striking examples seen below, Antonio added two youthful faces (folio 77 v.) and a small dancing man (folio 106 v.). It's not clear if he was sketching from life or copying other drawings, since one of the youths is wearing a Shakespearean-era ruff and the dancing man seems to wear an old-fashioned doublet. Did Antonio daydream about what life was like for his distant ancestors Guanentá and Francisco de Murcia?

Antonio Sánchez de Cozar Guanienta was not destined to alter the fields of science or timekeeping, but he left behind a vivid record of his mind. Not many of us could reason our way through an explanation of natural phenomena, but Antonio did a lot with his limited resources and exposure to learning. Perhaps somewhere up in the Empyrean sphere, Antonio can sense how his work on astronomy still fascinates us today.

Questions? Comments? Please email me at ruedafingerhut (at) gmail.com.

Comments

Post a Comment